Capital Beltway dot com

| Capital Beltway History |

|

The Capital Beltway is the 64-mile-long Interstate freeway that encircles Washington, D.C., passing through Virginia and Maryland, carrying the Interstate I-495 designation throughout, and carrying the overlapping Interstate I-95 designation on the eastern portion of the Beltway. |

|

Article index with links:

Introduction

Location and Design of Capital Beltway

Final Design of Capital Beltway

Naming of Capital Beltway

Naming and Construction of Capital Beltway Potomac

River Bridges

Construction of Capital Beltway in Maryland

Construction of Capital Beltway in Virginia

Opening Dates of Capital Beltway Segments

Major Environmental Issues in Construction of Capital

Beltway

Pavement Types on Capital Beltway

Completion of Capital Beltway

Route Numbering of Capital Beltway

Exit Numbering on Capital Beltway

Speed Limits on Capital Beltway

Capital Beltway Operation

Links

Formal planning for the Beltway began in 1950, and it was included as part of the national Interstate Highway System in the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 (which authorized the construction of a 41,000-mile national system of Interstate highways), and construction of the Beltway began in 1957. The most commonly used planning name for the highway was the Washington Circumferential Highway, and in June 1960 the highway was officially named "Capital Beltway" by both states. The I-495 Capital Beltway was fully completed when its final Maryland segment was opened to traffic on August 17, 1964.

|

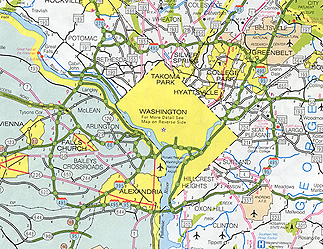

Capital Beltway is I-495, from MDOT SHA 2000 state map. Larger images - medium (235K), and large (469K). |

The Beltway made its first formal appearance on regional planning documents, when it appeared on maps and in a one-sentence reference in the 1950 “Comprehensive Plan” for the Washington area, by the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC). This document was published in 1952. The Maryland - National Capital Planning Commission (M-NCPC) approved the entire concept. In 1954 the planning board of Fairfax County, Virginia, approved a master highway plan that included the beltway, thus completing the official local approvals of the NCPPC plan for the beltway.

The Capital Beltway is 63.8 miles long, with 22.1 miles in Virginia, and 41.7 miles in Maryland. When originally completed, the Beltway was six lanes wide (three each way) for 49.3 miles between I-95 in Virginia, around the south, east and north of Washington, to the Virginia terminus of the northern Potomac River bridge, and the Beltway was four lanes wide (two each way) for 14.5 miles between the northern Potomac River bridge and I-95 at Springfield, Virginia. So all of the 41.7 miles of the Beltway in Maryland, including both Potomac River bridges, had six lanes; and in Virginia, 7.6 miles of the Beltway had six lanes and 14.5 miles had four lanes. All 33.7 miles of the Beltway east of the two I-95 junctions, had six lanes. The above lengths are to the tenth of a mile, and for convenience sake, in most places in this article, lengths are rounded to the nearest mile.

In the span of 1972 to 1992, through various widening projects, nearly the entire Beltway was widened to eight lanes (four each way), including the entire 14.5 mile section in Virginia that was originally four lanes. In 1972, Maryland completed Beltway widening to eight lanes (four each way) between MD-210 Indian Head Highway and MD-97 Georgia Avenue, a distance of 29 miles. In 1977, Virginia completed Beltway widening to eight lanes between US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway and VA-193 Georgetown Pike, a distance of 21 miles. In 1990, Maryland completed Beltway widening to eight lanes between MD-97 Georgia Avenue and I-270/MD-355, a distance of 4 miles. In 1991-92, Maryland and Virginia completed Beltway widening to eight lanes between I-270 Spur and VA-193, a distance of 5 miles; this included the American Legion Memorial Bridge and approaches to each interchange closest to the river, which was widened to 10 lanes. The 3 miles of Beltway between I-270/MD-355 and I-270 Spur is adequate at six lanes, as the traffic volume is about 1/2 of that of the adjoining sections of the Beltway. The only other Beltway segment not widened to at least eight lanes, was the southern Potomac River bridge (Woodrow Wilson Bridge), and 1/2 mile of Beltway on either end of the bridge, which was built with six lanes (three each way), although widening is now under construction and the Beltway will be reconstructed to a 10- to 12-lane highway for 7.5 miles between west of VA-241 Telegraph Road and east of MD-210 Indian Head Highway, including constructing a new 12-lane Woodrow Wilson Bridge.

Location and Design

of Capital Beltway

Maryland and Virginia highway officials needed to directly coordinate on the task

of determining the location of the two Potomac River bridges for the proposed

circumferential highway that would completely bypass the District of Columbia

and Arlington, and these two locations were conceptually determined as far back

as the early 1930s in studies by committees of highway officials and professional

planners from Washington, Maryland and Virginia, for proposed bypasses around

Washington; and these two crossings were proposed to be a bridge at Alexandria

and a bridge east of Great Falls, Virginia. These bridges needed to cross the

Potomac River at or near to a right angle to minimize the length of the bridge

as much as feasible, and they needed to be located at a place where each state

could build a high-speed highway approach to each bridge. The rest of the circumferential

highway was generally planned independently by each state, with little actual

coordination between the states. The proposed Washington circumferential highway

was formally approved locally in the actions in 1950 by the National Capital Park

and Planning Commission (NCPPC), in 1952 by the Maryland - National Capital Planning

Commission (M-NCPC), and in 1954 by Fairfax County and the City of Alexandria,

and federally as an authorized and funded Interstate highway in 1956, and the

approved alignment was fairly similar to what was ultimately constructed. The

Maryland State Roads Commission (SRC) administered the design, right-of-way acquisition,

and construction of the 41-mile Maryland section of the Beltway; the Virginia

Department of Highways (VDH) administered the design, right-of-way acquisition,

and construction of the 22-mile Virginia section of the Beltway; and the federal

Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) administered the design and construction of the one-mile

Potomac River bridge (Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge) at Alexandria. The SRC and

VDH basically did operate independently of each other from the final design phase

onward in the development of the Beltway, but at the same time, after the federal

1956 Interstate Highway System approval, they had a fairly clear picture of what

the other state would build, as far as the general corridor (say, 1-mile wide

corridor) where the other state would build the Beltway.

The "Yellow Book", formally named the General Location of National System of Interstate Highways, was published by the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) in 1955, and it showed the official preliminary location of the urban Interstate highways, along with the loop Interstates and spur Interstates that were in addition to the mainline Interstate highways. The Yellow Book was provided to members of the U.S. Congress as the debates were underway that would lead to the enactment of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 that authorized the construction of a national 41,000-mile Interstate Highway System.

See website

Scans from

the Yellow Book for the proposal for

Washington, D.C.,

which includes the Washington circumferential highway. It depicts the beltway

in generally the same corridor where it was ultimately constructed.

Each state built their Beltway segments to the national Interstate highway standards

that were current at that time, with generally similar design standards, and all

of the 64-mile Beltway was built to full freeway standards (divided highway with

at least two lanes each way, no at-grade crossings, and no adjacent direct land

access), and it was built with six lanes (three each way) except for the four

lane (two each way) 14.5 mile segment in Virginia between the northern Potomac

River crossing and I-95 at Springfield. While the highway was in final design

in the late 1950s, Virginia officials requested that BPR federal highway officials

approve a six-lane design on the entire 22-mile Virginia section of the Beltway,

but the BPR approved only four lanes on the above 14.5-mile segment, an action

that by the late 1960s was seen by many people to have been a mistake due to the

frequent peak period traffic congestion that had affected that segment by then,

although it can be argued that when the final design had to be frozen in preparation

for construction in the late 1950s, that the traffic projections justified no

more than four lanes on that segment, given the modest level of residential and

business development that existed at that time in Northern Virginia. The entire

eastern portion of the Beltway east of I-95 was built with six lanes (three each

way), so an ‘I-95 bypass’ section of the Beltway was built with six lanes from

the outset.

The six-lane portion of the Beltway east of the I-95 junctions actually did have several 1/4-mile-long lane drops from three lanes to two: where I-295 merged into the Inner Loop immediately before the Wilson Bridge, where the Inner Loop outer lane became a collector-distributor (C-D) roadway at US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway, where the Inner Loop outer lane became a collector-distributor roadway at VA-241 Telegraph Road, and where the ramps from US-1 merged into the Outer Loop immediately before the Wilson Bridge. The two locations with C-D roadways at interchanges had the outer mainline lane exiting into a one-lane C-D roadway, intercepting the ramps and loops, and the C-D roadway continued on and rejoined the mainline of the Beltway as the outer lane, so in one respect there were three directional lanes at these locations. The two instances of lane drops immediately before the Wilson Bridge did see the three mainline lanes briefly drop to two lanes so that the ramp could merge in and become the outer lane. All of these locations had mainline widening that was completed in 1973 (at I-295 and US-1) and 1977 (at VA-241) to provide at least three mainline lanes each way without lane drops.

There is one place still existing where the mainline Beltway roadway has a

lane drop from three lanes to two, for 1/4 mile on the Inner Loop where the two-lane

roadway from southbound I-270 merges into the Inner Loop roadway of the Beltway

near MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue.

Many of the original 38 Beltway interchanges were built with the cloverleaf design

(four ramps and four loops), and some were a modified cloverleaf design that included

one or more semi-directional (flyover) ramps. Each Interstate interchange (I-95

and I-66 in Virginia, I-95 and I-295 and both legs of I-270 in Maryland), was

entirely or mostly a semi-directional interchange. A few of the Beltway interchanges

were built with the diamond (four ramps) design.

Final Design of Capital

Beltway

Highway agencies and their hired engineering consultants in both Maryland and

Virginia, charted a completely new alignment for the beltway, because so few inter-suburban

roads existed in the mid-1950s that could have been upgraded to become part of

the route. No Potomac River bridges existed in the Washington metropolitan area

between Virginia and Maryland, so two completely new Potomac River bridges were

required for building a new beltway which would completely encircle and bypass

Washington and Arlington.

Micheal Baker Corporation

was the main engineering firm that performed the final design on segments of the

Capital Beltway in Maryland. Michael Baker by then was a nationally known engineering

firm that had designed many highway and bridge projects. The Maryland State Roads

Commission (SRC) selected Micheal Baker to design its portion of the Beltway,

beginning with the conceptual alignments drawn in 1952 by the M-NCPC before the

state had officially approved the project. The Pennsylvania-based firm opened

a branch office on the third floor of the new College Park Business Center, in

April 1954. The Baker office in College Park, Maryland, quickly obtained contracts

for many highway projects, from the SRC, the District of Columbia Department of

Highways, and the National Park Service. By 1957, according to an in-house newsletter,

Baker had completed designs on many Maryland and D.C. projects, and the design

projects underway at that time included 14 miles of the I-695 Baltimore Beltway,

the 45-mile Northeastern Expressway (I-95 northeast of Baltimore), and 38 miles

of roadway and 68 major structures (mainly bridges) on the Washington Circumferential

Highway. The Maryland segment of the beltway was planned to follow open corridors

as much as possible, to avoid heavily developed areas where possible, and in Prince

Georges County it was possible to avoid heavily developed areas, but in Montgomery

County that was not possible in every area as there were some segments with heavy

impacts to developed areas with many homes and businesses acquired for the highway

right-of-way; and a 2-mile beltway segment was built through Rock Creek Park over

the objections of state and federal public park agencies, something that probably

would not have been possible after Congressional enactment of the 1969 National

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), as one of the many things that NEPA did was to

make it virtually impossible to build a highway through major public parkland.

The alternative to the Rock Creek Park alignment would have been to locate the

highway on a straighter alignment about a mile to the north, which would have

been advantageous from a traffic engineering standpoint, but which was effectively

politically impossible as it would have passed through heavily developed and very

affluent residential sections of Bethesda. After NEPA, it is quite possible that

it would not have been possible to find a feasible location build that segment

of the Beltway if it had not already been built, and that would have left a missing

link in the Beltway between MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue and MD-97 Georgia Avenue.

Sources for above paragraph: Washington’s Main Street: Consensus

and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, by Jeremy Louis Korr, Dissertation

submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland,

College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor

of Philosophy, 2002. The Baker Engineer 3.8 (November 1957). Comments about

NEPA and Bethesda alternatives by Scott Kozel.

Howard, Needles, Tammen, and Bergendoff, today named

HNTB Corporation, was the main

engineering firm that performed the final design on segments of the Capital Beltway

in Virginia. The New York-based firm, which had designed several major post-World

War II turnpikes including the New Jersey Turnpike and the Maine Turnpike, was

contracted by the Virginia Department of Highways (VDH) to plan the alignment

of the entire 22 miles of Beltway in Virginia and to perform the final design

of the Beltway between the Woodrow Wilson Bridge and US-50 Arlington Boulevard.

VDH performed the final design in-house for the Beltway segment between US-50

and the northern Potomac River bridge. Howard, Needles, Tammen, and Bergendoff

was contracted by VDH in 1956 to perform a location routing study for Virginia’s

entire Interstate highway system, and regarding the Virginia portion of the Washington

circumferential highway, they wrote that this highway would be “an

entirely new facility, which neither supplements nor replaces any existing routes”,

and that “It is notable that this line follows virtually

the only open corridor through the area. To shift from this alignment would either

involve considerable property damage to heavily developed areas or require the

location of this route much further from Arlington and the Washington area.”

The U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) administered the design and construction

of the 1.1-mile Potomac River bridge (Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge) at Alexandria,

and contracted with Howard, Needles, Tammen, and Bergendoff, to perform the final

design of the bridge.

Sources for above two paragraphs: Washington’s Main Street:

Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation

by Jeremy Louis Korr. Interstate Highway System, Howard, Needles, Tammen,

and Bergendoff, for Virginia Department of Highways, 1956.

When the final link of the Beltway was completed and opened to traffic on Monday, August 17, 1964, it had already been officially named the Capital Beltway, and its route designation throughout was Interstate I-495. In the years after the proposed beltway route had officially made its first appearance on the 1950 planning maps of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC), and the 1952 planning maps of the Maryland - National Capital Planning Commission (M-NCPC), it had been referred to by a variety of names, including the Washington Circumferential Highway, Circumferential Highway, the circumferential, the belt road, the belt parkway, the inter-county freeway, the inter-county belt highway, the inter-county belt freeway, and the inter-county belt parkway. During the construction period of the Beltway, Maryland and Virginia officials separately made efforts to find a name which would be easy to speak and which would fit easily on roadway signs.

The Maryland State Roads Commission (SRC) first proposed the names "Colonial Beltway" and "Colonial Parkway" in March 1960, and then decided on the name "Capitol Beltway". Fairfax County, Virginia officials approved the name "Capital Ring", but state officials disagreed, as they wanted a name to honor George Washington or George Mason. Virginia officials then decided to name its Beltway section "Capitol Beltway", in agreement with Maryland officials. In the next few months, various officials and citizens pointed out that the word "capitol" refers to the building that houses the legislature (which is true for a state capital or for the U.S. capital), while the word "capital" refers to the entire capital city; so the proper word to name a highway that encircles Washington, D.C., would use "capital" and not "capitol", so on June 22, 1960 the highway was officially named "Capital Beltway" by both states, and that has been the official name since then.

Sources: "Maryland Picks Name for Highway," Washington Evening Star, March 13, 1960. "Board Can't Decide Highway's Name," Washington Post, April 14, 1960. "Capital Planners Right Capital Spelling Error," Washington Evening Star, June 23, 1960. "One Letter Changed In Name of Beltway," Washington Post, June 23, 1960. "New Capital Beltway Name Stirs Road Commission," Washington Evening Star, August 18, 1960. "Debate Appears Settled: It'll Be 'Capital Beltway'," Construction magazine, September 5, 1960.

Naming and Construction of Capital Beltway Potomac River Bridges

The Capital Beltway crosses the Potomac River in two places, a southern crossing at Alexandria, Virginia, and a northern crossing near Cabin John, Maryland. Each crossing connects Virginia and Maryland, and a small mid-span section of the southern bridge crosses an over-water corner of the District of Columbia. The closest local road access interchanges on each crossing are, for the northern crossing, in Montgomery County, Maryland, and in Fairfax County, Virginia; and for the southern crossing, in the City of Alexandria, Virginia, and in Prince Georges County, Maryland. The Virginia approach of the southern crossing is in the City of Alexandria, as 2/3 mile of the Beltway is in the City of Alexandria and the rest of the 22-mile Virginia section of the Beltway is in Fairfax County.

The construction of the original 5,900 foot long southern Potomac River crossing at Alexandria was authorized by the U.S. Congress on August 30, 1954, to be built and 100% funded by the federal government. It was initially named the Jones Point Bridge, and was officially named the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge, on May 22, 1956. Excerpts from "Why is the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge Named after Woodrow Wilson?", by the Rambler, a historian of FHWA (Federal Highway Administration).

On August 30, 1954, President

Dwight D. Eisenhower signed Public Law 83-704, "An Act to authorize and direct

the construction of bridges over the Potomac River, and for other purposes." One

provision stated:

The Secretary of the Interior . . . is authorized and directed

to construct, maintain, and operate a six-lane bridge over the Potomac River,

from a point at or near Jones Point, Virginia, across a certain portion of the

District of Columbia, to a point in Maryland, together with bridge approaches

on property owned by the United States in the State of Virginia.

The sum of $14,925,000 was authorized to be appropriated for the Jones Point Bridge. However, the cost of the approaches and improvements to collateral streets and highways was to be borne by the States of Maryland and Virginia:

On May 22, 1956, President Eisenhower signed Public Law 84-534, which transferred responsibility for the project to the Secretary of Commerce, whose Department included the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). The same day, the President signed Public Law 84-535, which renamed the "Jones Point Bridge" the "Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge."

Construction began on the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge in 1958. The six-lane Potomac River bridge and 3.2 miles of six-lane Beltway between US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway in Virginia and MD-210 Indian Head Highway in Maryland, opened to traffic on December 28, 1961. The bridge is most commonly publicly referred to by the shorthand name versions of Woodrow Wilson Bridge or Wilson Bridge.

FHWA By Day,

December 28, 1961, excerpt (blue text):

Secretary of Commerce Luther

Hodges, Administrator Rex Whitton, NPS Director Conrad Wirth, and State and local

officials participate in a ceremony opening the 5,900-foot Woodrow Wilson Memorial

Bridge, which will carry Capital Beltway traffic across the Potomac River. Mrs.

Woodrow Wilson, widow of the President, was to have unveiled a plaque in the memory

of her husband, but she is gravely ill. The bridge, which spans three jurisdictions

(Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia), was authorized when President

Dwight D. Eisenhower approved House Bill 83-704 on August 30, 1954. In 1958, BPR

began construction, which involved 13 contracts. The total cost of the bridge

was $14 million. Only short sections of the beltway on either side of the bridge

are open, but traffic on the bridge quickly reaches 18,000 vehicles per day.

See the link for an original photo of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge

(I-95/I-495 southern Potomac

River crossing).

The original Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge construction is documented here

with 14 photos on the official Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project website,

Project Scrapbook - Past Photographs Original Construction.

The under construction new twin-span 12-lane Potomac River bridge for the I-95/I-495 Beltway at Alexandria, will have the same name as the original bridge, the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge. The first new 6-lane Woodrow Wilson Bridge was opened to traffic in two stages in June and July of 2006, and it will be configured for 3 lanes each way until the 6-lane bridge for the Inner Loop of the Beltway opens to traffic in mid-2008. The original Woodrow Wilson Bridge was permanently closed to traffic on Saturday, July 15, 2006. When the new twin-span Woodrow Wilson Bridge is complete in mid-2008, it will then be jointly owned and administered by the states of Virginia and Maryland. An agreement was worked out in August 2001 by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Virginia and Maryland, to turn over the ownership of the new bridge, when it is completed, to joint ownership by Virginia and Maryland.

Many more details about the original and new Woodrow Wilson Bridge on Roads to the Future article: Woodrow Wilson Bridge (I-495 and I-95).

The construction of the Beltway's 1,450-foot-long northern Potomac River crossing near Cabin John, Maryland, was administered by the Maryland State Roads Commission (SRC) as a conventional Interstate highway project. The six-lane Potomac River bridge, and 7.0 miles of Beltway approaches between VA-7 Leesburg Pike in Virginia and MD-190 River Road in Maryland, opened to traffic on December 31, 1962. While an impressive bridge in its own right, it is much shorter than the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, and the Woodrow Wilson Bridge crosses a major shipping channel, while the northern crossing does not pass over a navigation channel, as the Potomac River is a shallow rocky river at that point. This northern crossing Beltway bridge did not have an official name until 1969, but it was commonly referred to as the Cabin John Bridge, a name that was "borrowed" from a nearby 200-foot-span stone arch aqueduct bridge that was opened in 1863 over Cabin John Creek in Montgomery County, Maryland, and this local bridge is still an aqueduct as well as carrying 2 lanes of MacArthur Boulevard. The 50th anniversary of the nation's largest military veterans organization was the occasion for the expression of Maryland legislative sentiment to name the Beltway bridge the American Legion Memorial Bridge, effective May 30, 1969, on Memorial Day. The public was slow in utilizing the new name, and for many years afterward many local people still called it the "Cabin John Bridge", although by the 1990s, it was most commonly publicly referred to as the American Legion Memorial Bridge, or by the shorthand name versions of Legion Bridge or American Legion Bridge.

Sources: "Bridge To Be Christened Officially But Quietly As Legion Memorial," Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1969. "Legion's Attention Span," Washington Post, May 31, 1986.

Construction

of Capital Beltway in Maryland

The first Beltway construction work began in February 1955 for a Beltway bridge

over Cedar Lane, just east of Wisconsin Avenue, inside of Rock Creek Park; and

this contract was for the bridge alone, with the approach roadways to be built

later. The first construction contract bids for the Beltway roadway were opened

in April 1956, for the 1.6 mile segment between Wisconsin and Connecticut Avenues

in Montgomery County, Maryland, which passes through Rock Creek Park; for a four

lane (two each way) highway built as a “parkway” (large trucks were banned), and

that segment opened to traffic on October 25, 1957, at a cost of almost $1 million.

The “Pooks Hill Interchange” between the Beltway and Wisconsin Avenue, was built

from February 1958 to November 1959, and included connecting segments of the Beltway,

Washington National Pike (US-240 freeway, later designated as I-70S, today’s I-270)

and MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue, and this comprised 4.2 miles of roadways and 6 bridges

and cost $2.3 million. The Beltway segment between MD-97 Georgia Avenue and MD-193

University Boulevard was placed under construction in 1960.

Sources for above: “Inter-County Road Belt Work to Start Despite

Park Dispute,” Washington Evening Star, February 20, 1955. “Bids

Asked for First Lap of Inter-County Beltway,” Washington Evening Star,

April 19, 1956. “First Section Dedicated of Circumference Road,” Washington

Evening Star, October 25, 1957. “Year’s Speedup In Beltway Set By Maryland,”

Washington Evening Star, November 2, 1960. Washington’s Main

Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral

dissertation by Jeremy Korr.

The Beltway segment between the Woodrow Wilson Bridge and MD-210 Indian Head Highway

was completed in 1961. The Woodrow Wilson Bridge and the 3.2 miles of Beltway

between US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway and MD-210 Indian Head Highway opened to

traffic on December 28, 1961, but opening ceremonies were canceled because of

33-degree weather and high winds, even though a group of officials and dignitaries

had assembled in the middle of the bridge before the proceedings were canceled.

The Maryland State Roads Commission (SRC) revised the proposed Beltway northern

Potomac River crossing alignment, which had been proposed to pass over Plummers

Island in the Potomac River near Cabin John, due to protests by the Washington

Biologists’ Field Club, who since 1901 had operated the island which was actually

owned by the U.S. Department of the Interior, and which is a 12-acre scientific

retreat; and the Beltway alignment was moved 200 yards further west, still passing

over a part of the island, but expected to have lower environmental impacts. Maryland

owns the Potomac River up to the Virginia shoreline, so Maryland’s highway program

paid for most of the $2.8 million cost of the Potomac River bridge, with Virginia

only responsible for the cost of the 20% of the length of the bridge that passes

over Virginia land.

The opening of the Beltway’s northern Potomac River crossing near Cabin John was

delayed by very cold weather, as it had been scheduled to open in early December,

1962, along with 7.0 miles of Beltway between VA-7 Leesburg Pike and MD-190 River

Road. The bridge opened to traffic “with absolutely no fanfare” on December 31,

1962, in 13-degree weather, with high winds blowing along the river, too cold

for any official ceremonies.

Sources for above: “Year’s Speedup In Beltway Set By Maryland,”

Washington Evening Star, November 2, 1960. “New Span to Unmask Jungle

Island,” Washington Evening Star, July 5, 1960. “Beltway Section,

Span to Open in December,” Washington Evening Star, August 19, 1962.

“Cabin John Bridge Opening Delayed,” Washington Evening Star, December

17, 1962. “Cabin John Span Opens On Cold, Quiet Note,” Washington Evening

Star, December 31, 1962. “65-mile Capital Beltway Opens,” Washington

Evening Star, August 16, 1964. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus

and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy

Korr.

The 3.2-mile Beltway segment between MD-190 River Road and MD-187 Old Georgetown

Road, in Montgomery County, opened to traffic without ceremony on November 15,

1963. A few weeks later, the 1.1-mile Beltway segment between MD-187 Old Georgetown

Road and MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue opened to traffic, and these segments completed

a continuous 11.3-mile Beltway section between VA-7 Leesburg Pike and MD-355 Wisconsin

Avenue, and it connected to the 1.6 mile segment between Wisconsin and Connecticut

Avenues that was the first section opened in October 1957, but this four lane

(two each way) “parkway” (large trucks were banned) section that makes a serpentine

path through Rock Creek Park, was closed to traffic in September 1963 for complete

reconstruction to six-lane (three each way) full Interstate standards (with all

vehicle types allowed), and it reopened in August 1964 when the final Beltway

segment was opened to traffic. This serpentine section of the Beltway has been

well-known to Washington commuters as the “Roller Coaster”. The 8.0-mile segment

of the Beltway in Prince Georges County, between MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue and

MD-210 Indian Head Highway, opened to traffic on July 17, 1964. The final link

of the Capital Beltway, in Montgomery County and Prince Georges County, Maryland,

was completed and opened to traffic on Monday, August 17, 1964, the 24.7-mile

section between MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue and MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Sources for above: “4 Mile Beltway Link is Opened Quietly,”

Washington Evening Star, November 15, 1963. “New Eight-Mile Section

of Beltway To Open in Prince Georges July 17,” Washington Evening Star,

July 5, 1964. “Closing the Ring”, Washington Post editorial, Monday,

August 17, 1964. “Ring Around the City”, Washington Evening Star,

August 16, 1964. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital

Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy Korr.

Construction

of Capital Beltway in Virginia

Construction of the 22-mile Virginia section of the Capital Beltway began three

years after Maryland’s, in April 1958, on the segment between VA-236 Little River

Turnpike and VA-617 Backlick Road. Construction moved forward within the next

few years on the rest, and there were delays until 1963 on the segment between

VA-7 Leesburg Pike and US-50 Arlington Boulevard due to difficulties in preparing

the contact for a bridge overpass over the Beltway for the Washington & Old Dominion

Railroad line. There were also difficulties in constructing the Beltway segment

through marshlands along the stream valley of Cameron Run along the southern border

of the City of Alexandria in the area where the Beltway has interchanges with

US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway and VA-241 Telegraph Road.

The first 6.7 miles of I-495 in Virginia opened to traffic on December 16,

1961, the section between I-95 Shirley Highway and US-50 Arlington Boulevard.

The 0.8 miles of I-495 in Virginia between US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway and the

state line, along with the Woodrow Wilson Bridge and Maryland segment to MD-210

Indian Head Highway (the segment comprised 3.2 miles in both states), opened to

traffic on December 28, 1961. On December 31, 1962, 4.7 miles of I-495 opened

to traffic between the state line at the northern Potomac River bridge, and the

VA-7 Leesburg Pike interchange, and this segment opening included the 2.3 miles

in Maryland to the MD-190 River Road interchange. The 3.2 miles of I-495 between

US-50 Arlington Boulevard and VA-7 Leesburg Pike opened to traffic on October

2, 1963. The last 6.7 miles of I-495 in Virginia, between I-95 Shirley Highway

and US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway, opened to traffic on April 2, 1964.

In the April 2, 1964, final segment opening of the 22-mile Virginia section of

the Capital Beltway, the opening ceremonies were held on the Beltway roadway 1/2

mile west of the I-495/US-1 interchange. It was another cold, wet and windy day,

a seeming hallmark of Capital Beltway openings, and over 200 attendees listened

to speeches by Virginia Department of Highways Commissioner (agency head) Douglas

B. Fugate, U.S. Bureau of Public Roads Chief Rex Whitton, and Virginia Governor

Albertis Harrison, and music by the 75th Army Band of Fort Belvoir. This segment

opening also marked the completion of the first Interstate highway statewide in

Virginia.

Sources for above: Lengths and opening dates from Interstate

System Opened to Traffic as of July 1, 1992, by Virginia Department of Transportation.

“Local,” Fairfax Herald, November 27, 1959. “The Capital Beltway,”

F.L. Burroughs, Virginia Highway Bulletin, January 1961. “Beltway Section,

Span to Open in December,” Washington Evening Star, August 19, 1962.

“Bids Let On Highway Projects,” Fairfax City Times, February 21,

1963. “Governor Harrison to Open Beltway,” Fairfax City Times, March

27, 1964. “22 Miles of Beltway Open Today,” Douglas B. Fugate, Annandale

Free Press, April 2, 1964. “Final Virginia Stretch of Beltway is Opened,”

Northern Virginia Sun, April 3, 1964. “Beltway Opening Ceremonies,”

Fairfax Herald, April 10, 1964. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus

and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy

Korr. [Douglas B. Fugate at that time was the Virginia Department of Highways

(VDH) Commissioner (agency head), and F. L. Burroughs was the VDH State Construction

Engineer (administrator of the VDH Construction Division).]

Opening Dates of Capital Beltway Segments

The following table summarizes the segment openings detailed in the previous two article sections. The first segment opened in 1957, as noted previously, and was closed, rebuilt to a higher design, and reopened in the final segment opening, so the table below counts that 1.6 miles of length twice; so it is table segments 2 through 10 that add up to the total 63.8 mile length of the Beltway.

|

Capital Beltway - Segment Openings | ||

Segment |

Length |

Date |

MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue - MD-185 Connecticut Avenue |

1.6 |

Oct. 1957 |

I-95 Shirley Highway - US-50 Arlington Boulevard | 6.7 |

Dec. 1961 |

MD-210 Indian Head Highway - US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway (includes Wilson Bridge) | 3.2 |

Dec. 1961 |

VA-7 Leesburg Pike - MD-190 River Road (includes Legion Bridge) | 7.0 |

Dec. 1962 |

US-50 Arlington Boulevard - VA-7 Leesburg Pike | 3.2 |

Oct. 1963 |

MD-190 River Road - MD-187 Old Georgetown Road | 3.2 |

Nov. 1963 |

MD-187 Old Georgetown Road and MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue | 1.1 |

Dec. 1963 |

US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway - I-95 Shirley Highway | 6.7 |

April 1964 |

MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue - MD-210 Indian Head Highway | 8.0 |

July 1964 |

MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue - MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue | 24.7 |

Aug. 1964 |

Major Environmental

Issues in Construction of Capital Beltway

Most of the Capital Beltway was built in areas where the soil is dry enough

and has a high enough content of clay and/or rock that in its natural state the

soil provided a good base for building a highway. For the most part, the topography

and soil geology of suburban Maryland and Northern Virginia was conducive to standard

highway engineering and construction techniques. The Beltway is located in two

geologic provinces, neither of which was particularly challenging to road builders.

Much of the eastern half of the Beltway is in the Coastal Plain, which is a gently

undulating plain that extends along the Eastern Seaboard from Mexico to New Jersey,

and it is characterized by tidal estuaries such as rivers and bays including the

Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, and the terrain gradually rises in elevation

from the Atlantic Ocean westward to hills up to about 400 feet above sea level

in elevation near its western boundary. The geologic province immediately to the

west is the Piedmont, which is a band of rolling hills with rocks just below the

surface, running from Alabama to New York, and its elevations range from sea level

to about 1,000 feet above sea level. The Piedmont is bounded to the west by the

Triassic Lowland province. The boundary between the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont

generally bisects the District of Columbia and the Capital Beltway from southwest

to northeast. The topography and geology of both provinces posed relatively few

challenges to the designers of the Beltway.

Source: Natural Features of the Washington Metropolitan Area, Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG), 1968. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy Korr.

There were difficulties in constructing the six lane (three lanes each way) Beltway segment through marshlands along the stream valley of Cameron Run near the southern border of the City of Alexandria in the area where the Beltway has interchanges with US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway and VA-241 Telegraph Road. Like many stream valleys, the soil has a high amount of organic material and has a high water content, so the soil is compressible and in its natural state is inadequate for supporting a highway. The natural channel of Cameron Run meandered north and south of the Beltway right-of-way between VA-241 and US-1, and on the mid-section of that segment, the channel of Cameron Run was relocated to a straight channel alongside the south edge of the Beltway. On large parts of that Beltway segment, borrow excavation (select soil backfill) was deposited to provide the base of the Beltway roadways. Part of the ramps and roadways at the I-495/US-1 interchange were built on bridge structure over marshlands and open water.

The above design, like building the 2-mile Beltway segment through Rock Creek Park in Montgomery County, Maryland, most likely would have been impossible to build after enactment of the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), with its stringent federal environmental standards. Unfortunately, these kind of highway designs were commonplace all over the U.S. before NEPA, as the rationale was that it enabled urban and suburban highway segments to be built in places that did not displace houses and businesses; engineers and planners routinely routed highways through areas which would provide the least resistance, and in practical terms that often meant sites that were occupied by minorities or the poor, or riverfronts or stream valleys or parks that housed few or no residents or business owners to complain. After NEPA, many such highway segments were able to be built without filling in marshlands and streams, but only by placing the highway on bridge structures that passed over those natural resources, even though financially that made the highway segment much more expensive to build than if it was built on earthen fill. Such a post-NEPA design would have placed most of the 1.3 miles of Beltway between VA-241 and US-1 on bridge structure, from about 1/4 mile east of VA-241 to 1/4 mile east of US-1, plus nearly all of the I-495/US-1 interchange; and the stream channel of Cameron Run would have been left in its natural place.

Building the Beltway segment between VA-241 and US-1 as it was historically constructed, posed considerable engineering challenges. A “sand drain” process was utilized, to remove most of the water from the soil from the surface to about 50 feet under the ground surface, and a “sand blanket” was placed overtop of the ground surface to act as a “sand wick” to gradually draw the excess water out of the soil below, so that the soil would be incompressible enough to support a highway embankment. The engineering firm who designed a segment of the New Jersey Turnpike through the Meadowlands near Newark in the late 1940s, faced a similar soil situation, and they were hired by HNTB to design this segment of the Beltway.

VDH engineer F.L. Borroughs wrote about this design procedure in 1961 (quote

in blue text):

From this interchange westward along 413, the roadway is completely in marshland. To provide stability and underbearing for the beltway, a construction process new to the Department was undertaken. A contract has been awarded for the construction of a sand-drained embankment utilizing vertical sand drains for the consolidation of the super-saturated marsh land. Imagine a semi-solid mass of soil and water with a soil blanket several feet in thickness placed uniformly over the entire surface. Obviously, owing to its heavier unit density, the blanket will displace the super-saturated marsh material. Because of the overload conditions, a hydrostatic pressure is built up within the semi-solid beneath the overload blanket.

Imagine, next, the tapping of vertical drains of porous material into this high pressure area, and the draining of water, with resultant loss in pressure and consolidation of the semi-solid results. The source of the sand and some hydraulic backfill is a pit two miles downstream in the Potomac River.

Sources for above: "The Capital Beltway," by F.L Burroughs, Virginia Highway Bulletin, January 1961. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy Korr. Includes analysis and commentary by Scott Kozel.

FAP 413 was Virginia’s original route number for its section of the Capital Beltway.

The 21-mile Beltway eight-lane widening project in Virginia from 1974 to 1977, included the widening of this segment from six lanes (three each way) to eight lanes (four each way), and a strip of the above sand wick/drain process along the outside of each roadway was constructed in order to widen the roadway embankment to the required width.

The current Woodrow Wilson Bridge project includes the widening of this Beltway segment to 12 lanes, and there are ground improvement contracts included to provide the necessary foundation for the roadways. This involves a similar sand wick/drain process as was done in the previous projects, but includes stronger treatments that include “soil cement pillars” whereby a pattern of columns of cement treated soil were constructed beneath the roadways, by mixing a small amount of cement in with the soil to make the ground considerably stronger from a load bearing standpoint. This should make the ground under the Beltway roadways much more resistant to any settling in the future. The Beltway Outer Loop local roadway is located partway across the northern bank of Cameron Run, so it was built on a bridge structure rather than fill in any of Cameron Run with earthen embankment.

Pavement Types on Capital Beltway

Asphalt concrete, commonly known simply as asphalt, also sometimes called blacktop or hot-mix asphalt, is a composite material commonly used for construction of highway pavement and parking lots. It consists of a liquid asphalt binder and mineral aggregate (generally gravel plus sand) mixed together at about 300 degrees Fahrenheit (about 150 degrees Celsius) then laid down in layers and compacted.

Concrete is a construction material that consists of cement (commonly Portland cement), aggregate (generally gravel plus sand), water, and admixtures. Concrete solidifies and hardens after mixing and placement, due to a chemical process known as hydration. The water reacts with the cement, which bonds the other components together, creating a stone-like material. Portland cement concrete is also called hydraulic cement concrete. The concrete utilized on highway roadways and bridges, is reinforced internally with a grid of steel bars, and the term ‘reinforced concrete’ refers to concrete that is reinforced (given additional strength) in this manner.

Today the entire Beltway mainline roadway (excepting some bridges) has a riding surface of asphalt concrete. The bridges in the Beltway mainline all have a roadway deck constructed of reinforced Portland cement concrete, and on many of them that is the vehicle riding surface, although some of them have an asphalt concrete surface layer that is the riding surface. The current Woodrow Wilson Bridge and American Legion Bridge have a riding surface of reinforced Portland cement concrete.

Along most of the length of the Beltway, there is an original reinforced Portland cement concrete pavement underneath the asphalt concrete surface, and that original concrete pavement has a slab thickness of 8 to 9 inches, depending on the section, and that was the original riding surface; and after several decades of wear it was overlaid with asphalt concrete. When overlaid, the Portland cement concrete pavement was repaired first to fix the damaged sections, and then several layers of asphalt concrete totaling at least 5 to 6 inches in depth was placed on top of the Portland cement concrete pavement, resulting in a strong smooth pavement structure.

The original Virginia Beltway pavement types are as follows. The 21-mile Virginia section of the Beltway between the American Legion Bridge and VA-241 Telegraph Road, had reinforced Portland cement concrete pavement. When it was widened to eight lanes (four each way) 1974-1977, the reinforced Portland cement concrete pavement was widened the necessary width for the new traffic lanes, the shoulders were underlaid with 6 inch depth plain Portland cement concrete, and the entire roadway and shoulders were overlaid with a 6 inch depth asphalt concrete riding surface (per review of construction plans by Roads to the Future author and observation during construction). The 1.3 mile Virginia section of the Beltway between VA-241 Telegraph Road and the Woodrow Wilson Bridge was originally constructed with asphalt concrete, due to the fact that the segment was built on earthen embankment fill through a stream valley and marshlands, and the principle was that would be a better design to handle any settling of the roadway by adding a few inches depth of asphalt concrete overlay in a section that settled.

The original Maryland Beltway pavement types are as follows. The 31-mile Maryland section of the Beltway between the Woodrow Wilson Bridge and MD-97 Georgia Avenue, originally had reinforced Portland cement concrete pavement, and when the 29-mile section between MD-210 Indian Head Highway and MD-97 Georgia Avenue was widened from six lanes (three each way) to eight lanes (four each way) in 1970-1972, one reinforced Portland cement concrete lane each way was added on the inside of each directional Beltway roadway. This section of the Beltway was overlaid with asphalt concrete with at least 5 to 6 inches in depth, in the 1980s. The 10-mile Maryland section of the Beltway between MD-97 Georgia Avenue and the American Legion Bridge, originally had asphalt concrete pavement, and the later widening projects utilized the same paving material. The shoulders on the Maryland section of the Beltway have always utilized asphalt concrete throughout.

The various connecting roads and highways that interchange with the Beltway, had the interchanges and connecting roads built along with the Beltway. The ramps typically were constructed with the same pavement material as that section of the mainline Beltway. The connecting roads and highways were in most cases constructed with asphalt pavement.

The current Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (2000-2011) includes the widening of 7.5 miles of the Beltway to 10 to 12 lanes, between west of VA-241 Telegraph Road and east of MD-210 Indian Head Highway, and the all land roadways and ramps in this segment will be completely replaced with new roadways and ramps, and the land roadway paving material will be full-depth asphalt concrete pavement, throughout the project. All bridges on the project will be replaced with new bridges, and the riding surface of the roadway decks will be reinforced Portland cement concrete.

The final link of the Capital Beltway, in Montgomery County and Prince Georges County, Maryland, was completed and opened to traffic on Monday, August 17, 1964, the 24.7-mile section between MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue and MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue Extended.

FHWA By Day,

August 17, 1964, excerpt (blue text):

Near the New Hampshire Avenue interchange, Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes

cuts a ribbon officially opening the Capital Beltway around Washington, DC. He

calls it a "road of opportunity." Administrator Rex Whitton calls it a "huge wedding

ring for the metropolitan area", while Representative Carlton R. Sickles (MD)

makes the day's briefest speech: "I'm so happy, I can't express myself."

See the link for 1964 photos of the Capital Beltway, including a photo

of the American Legion Memorial Bridge (I-495 northern Potomac River crossing).

A variety of local newspaper articles around that day had many positive things

to say about the Beltway, as at that point a complete freeway bypass of the Washington

area would exist for the first time, and nobody yet knew how crowded that the

Beltway would become before the end of the decade.

The term “District” is a common shorthand word used to refer to the District of

Columbia.

“New Road to Bring Vital Area Changes”, Washington Post, August

16, 1964. Excerpts (in blue text):

There is a temptation to describe the belt road as the Washington area’s new “Main Street”. But it isn’t. In reality, it is a contemporary version of a crosstown boulevard, joining suburban areas that have more in common with each other than they ever suspected. Yet the Beltway travel pattern is a random one. Nobody will want to go simply from one point on the Beltway to another. Every trip will start at some distance from the Beltway, will use it for two miles or 20, then will get off to reach the driver’s destination.

For years, Fairfax and Montgomery counties were strangers – the only link

between them being via Washington. Today these counties, with similar economic and social characteristics, are so close that a journey between has become routine – and the merchants of both counties know it. Even more strikingly, the Beltway provides the first truly good connection between the two suburban Maryland counties, Montgomery and Prince Georges. Similarly, it joins Bethesda and Silver Spring.

National Capital Planning Commission

(NCPC) is today's name for the above federal planning agency. In 1926, Congress

renamed the agency the National Capital Park and Planning Commission and additionally

charged the agency with comprehensive planning responsibilities for the capital.

From

History

of NCPC (blue text):

With the passage of the 1952

National Capital Planning Act, Congress once again renamed the agency, this time

as the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), the name the agency bears

today. Congress designated NCPC as the central planning agency for the federal

and District of Columbia governments for the National Capital Region, an area

identified in the Planning Act. Congress also reiterated its charge to NCPC to

preserve the region's important natural and historical features. The last major

change to NCPC's mandate occurred in 1973 when Congress passed the District of

Columbia Home Rule Act. The Act delegated the planning responsibility for the

District of Columbia to the city's mayor. The Home Rule Act maintains NCPC's role

as the central planning agency for federal land and buildings in the National

Capital Region, with an advisory role to the District for certain land use decisions.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 by Congress authorized the construction of

the national 41,000-mile Interstate Highway System, with 90% federal aid funding

from the U.S. Highway Trust Fund, and the proposed 64-mile-long Washington beltway,

which had not yet been named the Capital Beltway, was included in the Interstate

system. In 1957 and 1958, design, right-of-way acquisition and construction, quickly

moved forward on the beltway, and it was given the route designation of I-495.

The entire Beltway was completed on the aforementioned date in August 1964.

“Tawes Snips a Ribbon, Opening D.C. Beltway”, Washington Post, August

18, 1964. Excerpts (in blue text):

With a symbolic snip

from a pair of golden scissors, Maryland Gov. J. Millard Tawes cut a ribbon yesterday

and officially opened the 66-mile Capital Beltway. Several thousand persons gathered

for the ceremony near the New Hampshire Ave. interchange of the $189-million highway

and appeared to enjoy the self-inflicted traffic jam that followed the opening.

Gov. Tawes predicted it would be a “road of opportunity” for the State and the

Nation and expressed hope that the four-and-six-divided highway would reduce traffic

accidents.

Federal Highway Administrator Rex M. Whitton, who shared ribbon-cutting honors with the Governor, said that the highway is a “huge wedding ring for the metropolitan area, meeting all of its suburbs.” Rep. Carlson R. Sickles (D-Md.) made the briefest speech of the day. “I’m so happy I can’t express myself,” he said.

The article said that there were dozens of officials introduced during the opening ceremony, from Maryland, Virginia, and D.C. Even though it was a Maryland highway opening, there were many officials from both sides of the Potomac River, from both state capitals, from the District of Columbia, and from the federal government.

From Rex Whitton's speech, "The Minus-Ten-Minute

Road", August 17, 1964:

This route means many things

to many people... For Interstate 495 is an integral part of the 41,000-mile Interstate

Highway System... Interstate 495 is also a mighty traffic circle, 61 miles around

and 17 miles in diameter. It will provide a swift channel for through travel,

whether truck, bus or car. Since it will take them off their present routes through

the heart of the city, it will help relieve Washington's in-town traffic congestion,

too. Interstate 495 is also a huge wedding ring for the metropolitan area, uniting

all of its suburbs. We can be better neighbors - and have better opportunities

for employment, recreation, and shopping. And Interstate 495 is the breeding ground

for the region's economy.

Address at Opening of the Capital Beltway, Interstate 495, by Governor Tawes, from Executive Records, Governor J. Millard Tawes, 1959-1967, Volume 82, Volume 2, Page 582-584, from Maryland State Archives. Full quote (in blue text):

|

Route Numbering of Capital Beltway

Following the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 by Congress that authorized the construction of the national 41,000-mile Interstate Highway System, including the proposed 64-mile-long Washington circumferential highway, the entire beltway was granted the Interstate Route I-495 designation by federal and state highway officials.

Three-digit Interstate routes have a leading digit with the last two digits being the mainline route that it supplements, so I-x95 routes would have routes such as the ones in Virginia, I-195, I-295, I-395 and I-495. An odd-number leading digit signifies a spur route off a mainline route (examples are I-195 and I-395). An even-number leading digit signifies a loop around a city (examples are I-295 and I-495), or a branch route connecting two Interstate highways (an example is I-270 in Maryland). Three-digit Interstate route numbers can duplicate, but not in the same state.

The completed Beltway was designated I-495 throughout from 1964 to 1977. In 1977, the eastern portion became I-95, and Shirley Highway inside the Beltway was changed from I-95 to I-395. This was done because of the cancellation of proposed I-95 from New York Avenue in the District of Columbia northward into Prince George's County, Maryland, to I-495. The I-95 designation was moved to the eastern half of the I-495 Beltway in 1977, and I-495 was removed from the eastern half of the Beltway, and I-395 replaced the I-95 designation on Shirley Highway from I-495 to the 14th Street Bridge, on the 14th Street Bridge itself, on the Southwest Freeway in D.C. and on the Center Leg Freeway in D.C. Today's I-395 is the former segment of I-95 inside of the Beltway.

Many regional motorists never fully adjusted to having a full-circle beltway with halves with two different numbers (I-95 and I-495). In 1991, the I-495 designation was applied back to the eastern portion of the beltway, so the whole Beltway is again I-495, and the eastern portion is I-95 also (it carries both I-95 and I-495). The Beltway has the clockwise direction (as in looking at a map of the Beltway) signed as the Inner Loop, and the counter-clockwise direction is signed as the Outer Loop.

Exit Numbering on Capital

Beltway

The exit (interchange) numbering on the Beltway began with a sequential

system in 1964 when the Beltway was fully complete, and it was a somewhat hybrid

system from 1980 to 2000, and in 2000 was finalized to a fully milepost-based

system that should last permanently. The original exit numbering system was sequential

numbering from 1 to 38 (there were no “number gaps” except for future Exit 22

that later was canceled), starting at Exit 1 at US-1 in Alexandria, running clockwise

as viewed on a map from above, advancing around the south, west, north and east

of Washington, ending at Exit 38 at I-295 near the Wilson Bridge.

The official decision in 1977 to cancel the remaining unbuilt segments of I-95 in the District of Columbia and Maryland, and the concurrent decision to move the I-95 designation to the eastern portion of the Beltway, was the cause of the need to renumber the exits on the Beltway.

The period of the 1980s and later was also a time when many states changed their Interstate highway exit numbering from sequential numbering to milepost-based numbering. Sequential exit numbering means that the exit numbers increase consecutively (1, 2, 3, 4, etc., in sequence) one by one along the highway. Milepost-based exit numbering means that each exit number is the same as the number of the nearest milepost, and while the numbers are not consecutive (for example if four exits in sequence were at mileposts 7, 9, 11 and 15, then those would be the respective exit numbers), milepost-based exit numbering has widespread public support because it makes it easy to compute how many miles one needs to travel from where they are currently, to reach their destination exit, although the fact that exit numbers usually start over at zero at the beginning of each state border, removes that advantage for an inter-state trip.

Maryland began instituting milepost-based exit numbering on its Interstate highways about 1980, and specifically on the Capital Beltway in 1980. The federal standard for exit numbering on Interstate highways, is for the numbering to advance from south to north on north-south highways, and from west to east on east-west highways. Since the eastern portion of the Beltway was I-95 alone at that point, Maryland posted milepost zero at the state border at Alexandria, and advanced the milepost numbers along I-95 all the way to Delaware. At the I-95/I-495 junction north of Washington at Milepost 27, Maryland continued that same increasing milepost sequence from 27 to 42 along the I-495 Beltway all the way to the Virginia shoreline at the Legion Bridge near Cabin John, Maryland. Each Beltway interchange in Maryland was given milepost-based exit numbering, so from 1980 and onward there were exits 2 through 41 in Maryland, running counterclockwise as viewed on a map from above. This is opposite of the Beltway’s original clockwise exit numbering system. Virginia’s Beltway exits remained in the original system of running clockwise sequentially from 1 to 14, so the two states had their exit numbers advancing in the opposite direction, and each state had a Beltway exit for the numbers 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, and 11. Maryland’s Beltway exit numbering system has not changed since 1980.

In 1981, Virginia renumbered its exits 1 through 4 to 58 through 61 to be consistent with the rest of its sequential exit numbering on its I-95, and while this eliminated the duplication of Beltway exit numbers 2, 3 and 4 in both states, it created three unrelated exit numbering schemes on the Beltway. A 1981 Washington Post editorial called this an “atrocity,” that resulted in “two unrelated sets of Virginia Beltway exit numbers, going in opposite directions,” and “two unrelated sets of exit numbers (between Maryland and Virginia), going in opposite directions.” A couple years later Virginia reverted those exit numbers back to 1 through 4 to reduce the Beltway exit numbering schemes back to two.

In 1991, the two states decided to apply I-495 back to the I-95 eastern portion of the Beltway. In 1987, the two states agreed to post along the Beltway signs with a Capital Beltway logo in red, white and blue, with an image of the U.S. Capitol building surrounded by a circle, and the Beltway terms “Inner Loop” and “Outer Loop” came into use then, “Inner Loop” for the clockwise-running roadway, and “Outer Loop” for the counterclockwise-running roadway. Looking at the Beltway on a map from above, the loop of the clockwise-running roadway is inside of the loop of the counterclockwise-running roadway, hence the terms “inner” and “outer” for the concentric roadways of the Beltway.

Virginia did not convert its statewide Interstate highway exit numbering system from sequential numbering to milepost-based numbering until beginning in 1992, and the Beltway exits were renumbered in 2000. At that time it was decided to continue Maryland’s I-495 mileposting from Maryland’s Milepost 42 at the Virginia shoreline at the Legion Bridge near Cabin John, to a new Milepost 57 at the I-95/I-395/I-495 Springfield Interchange; and to continue I-95’s mileposting (170 through 177) along the I-95/I-495 section of the Beltway from I-95/I-395/I-495 Springfield Interchange to the state border at the Wilson Bridge at Alexandria.

When exit numbers were changed in these various renumberings, new exit number signs were installed, and each exit changed would carry an “Old Exit nn” sign for a year after the change, to assist motorists in adjusting to the change.

The current Beltway exit numbering system should be permanent, as it follows the milepost-based Interstate highway exit numbering system in both states, which should be permanent. There is no foreseeable reason why the Beltway exit numbering system should see any more changes (the future completion of the canceled original downtown route of I-95 through the District of Columbia is not impossible but is highly unlikely). It is a shame that it took from 1980 to 2000 to fully change the Beltway’s original sequential exit numbering system based on I-495 alone, to the current milepost-based exit numbering system based on I-495 and its eastern I-95 overlap. This underscores the inadequate Beltway coordination between the two states, at times, that has impacted the management of what is one metropolitan circumferential freeway. It could be argued that Virginia was remiss for not immediately following Maryland’s 1980 change in its Beltway exit numbering system, by installing the same system on its portion of the Beltway, but it could also be argued that Maryland was presumptuous for imposing milepost-based exit numbering on its section of the Beltway at a time when Virginia was not interested in imposing milepost-based exit numbering on its Interstate highways (and wasn’t until starting 12 years later, which was Virginia’s prerogative).

Sources: “Beltway Bandits,” Washington Post editorial, April 29, 1981. “New Signs to Put Beltway on Road to Easier Travel,” Washington Post, October 8, 1987. “Beltway Heads Toward a Unified Designation: I-495,” Washington Post, April 18, 1991. “Vote on Numbering Will Mean a Less Loopy Beltway,” Washington Post, June 11, 1991. “New Beltway Exit Numbers Won’t Have You Scratching Your Head,” Washington Post, October 16, 2000. Washington’s Main Street: Consensus and Conflict on the Capital Beltway, 1952-2001, doctoral dissertation by Jeremy Korr. Official state maps from 2007 and the 1960s. Includes analysis and commentary by Scott Kozel.

The Capital Beltway when completed in 1964 had 37 interchanges, and in 1971 that number increased to 38 when I-95 in Maryland was completed to the Beltway. These two pairs of Beltway junctions were each defined as a single interchange in the original exit numbering system -- I-70S and MD-355, and MD-190 and Cabin John Parkway; and in Maryland's exit renumbering, each in those pairs has a separate exit number; and it is a matter of definition as to whether each of those pairs should be considered to be one interchange or two interchanges. The 4 interchanges marked in the table below as "n/a" for Original Number, did not exist when the Beltway was completed in 1964, were not planned at that time, and were all constructed after 1990. The Beltway as exit-numbered in 2007 has 44 interchanges.

|

Capital Beltway - Interchange Numbering | ||

Current Number |

Connecting Road |

Original Number |

2 |

Interstate 295 Anacostia Freeway / (future) National Harbor |

38 |

3 |

MD-210 Indian Head Highway |

37 |

4 |

MD-414 Saint Barnabas Road |

37A |

7 |

MD-5 Branch Avenue |

36 |

9 |

MD-337 Allentown Road / Andrews Air Force Base |

35 |

11 |

MD-4 Pennsylvania Avenue |

34 |

13 |

Ritchie-Marlboro Road |

(n/a) |

15 |

MD-214 Central Avenue |

33 |

16 |

Arena Drive / FedEx Field |

(n/a) |

17 |

MD-202 Landover Road |

32 |

19 |

US-50 John Hanson Highway |

31 |

20 |

MD-450 Annapolis Road (original name was Defense Highway) |

30 |

22 |

Baltimore-Washington Parkway |

29 |

23 |

MD-201 Kenilworth Avenue |

28 |

24 |

Metrorail Greenbelt Station |

(n/a) |

25 |

US-1 Baltimore-Washington Boulevard |

27 |

27 |

Interstate 95 |

26 |

28 |

MD-650 New Hampshire Avenue |

25 |

29 |

MD-193 University Boulevard |

24 |

30 |

US-29 Colesville Road |

23 |

- |

Northern Parkway (unbuilt) | 22 |

31 |

MD-97 Georgia Avenue |

21 |

33 |

MD-185 Connecticut Avenue |

20 |

34 |

MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue / Rockville Pike |

19 |

35 |

Interstate 270 (originally was I-70S) |

19 |

36 |

MD-187 Old Georgetown Road |

18 |

38 |

Interstate 270 Spur (originally was I-270) |

17 |

39 |

MD-190 River Road |

16 |

40 |

Cabin John Parkway |

16 |

41 |

Clara Barton Parkway (originally MD's George Washington Memorial Parkway) |

15 |

43 |

George Washington Memorial Parkway |

14 |

44 |

VA-193 Georgetown Pike |

13 |

45 |

Dulles Airport Access Road and VA-267 Dulles Toll Road |

12 |

46 |

VA-123 Chain Bridge Road |

11 |

47 |

VA-7 Leesburg Pike |

10 |

49 |

Interstate 66 |

9 |

50 |

US-50 Arlington Boulevard |

8 |

51 |

VA-650 Gallows Road |

7 |

52 |

VA-236 Little River Turnpike |

6 |

54 |

VA-620 Braddock Road |

5 |

57 |

Interstates 95 and 395 - Shirley Highway |

4 |

173 |

VA-613 Van Dorn Street |

3 |

174 |

Eisenhower Avenue Connector |

(n/a) |

176 |

VA-241 Telegraph Road |

2 |

177 |

US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway |

1 |

Speed Limits on Capital Beltway

Since the 1973 National Maximum Speed Limit act was enacted, which mandated a

maximum speed limit in the U.S. of 55 miles per hour, no segment of the Capital

Beltway has had a higher speed limit than 55 mph. In 1987 the NMSL was modified

to allow 65 mph on rural Interstate highways, and the Beltway was ruled to be

in a metropolitan area (and not rural) and still subject to a federal maximum

of 55 mph. In 1995 the U.S. Congress abolished the national maximum speed limit,

and returned the setting of speed limits back to state control as was the case

before 1973, thus making it possible to have higher speed limits on the Beltway.

The Roads to the Future author has clear recollections of what the

speed limits were on the Capital Beltway before 1973, having lived at that time

in Alexandria less than a mile from the I-495/US-1 interchange, and a frequent

Beltway user. The vast majority of the length of the Beltway was geometrically

designed for 70 mph. Both Potomac River bridges and their immediate approaches

had a speed limit of 60 mph. The 21 miles of Beltway in Virginia, between within

1/2 mile of each Potomac River bridge, had a speed limit of 65 mph for cars and

55 mph for trucks. The 29 miles of Beltway in Maryland between 1/2 mile of the

Woodrow Wilson Bridge and MD-97 Georgia Avenue, had a speed limit of 70 mph for

cars and 60 mph for trucks. Just west of MD-97, the speed limit dropped to 60

mph, and in the 2-mile serpentine section in Rock Creek Park the speed limit was

50 mph. The 8 miles of Beltway between MD-355 Wisconsin Avenue and 1/2 mile into

Virginia, had a speed limit of 60 mph. The above cites of a single speed limit

for a section, denotes that there was no car/truck speed limit differential on

that section.

The I-495 Capital Beltway opened in 1964 to much optimism and enthusiasm. By 1968 and 1969, traffic volumes of cars and trucks had grown to the point where the highway was always well-used, with traffic volumes during peak hours approaching the capacity of the highway on various sections, and the maximum segment volume then was about 80,000 vehicles per day.

Today much of the Beltway carries over 200,000 vehicles per day, and even with major widening projects between 1972 and 1992, making nearly the entire Beltway eight lanes wide (four each way), much of the Beltway experiences major congestion for major periods of each day.

This article will have much more added in the future to chronicle the history of the Beltway.

Links

For more information, see

Roads to the Future

articles:

Capital Beltway

(I-495 and I-95)

Springfield Interchange Project

Woodrow

Wilson Bridge (I-495 and I-95)

I-495 Capital Beltway by Mike Hale. History, information and exit list.

Copyright © 2007 by Scott Kozel. All rights reserved. Reproduction, reuse, or distribution without permission is prohibited.

By Scott M. Kozel, Capital Beltway dot com, Roads to the Future

(Created 8-20-2007, last updated 11-20-2007)